I’m not sure why I agreed to take a job without the promise of being paid. But when you’re thirteen, you don’t have much bargaining power.A modest income was promised to young boys (occasionally girls) by the publishers of The Conshohocken Recorder and The Weekly Advertiser, two minuscule newspapers published in the Philadelphia suburbs, probably not that different from many other local papers at the time. The way the income was earned by those who delivered it, however, was unusual.It’s hard to imagine a time when anyone would want to read these weekly ten-page tabloids. As its name suggests, The Advertiser was crammed with ads for local businesses, next to brief articles about local doings. The Recorder, I guess, recorded local news, but like its competitor, supported itself by advertising the same pizzerias, barbershops, and insurance agencies that placed identical ads in our local church bulletin.Decades before the internet, there were far fewer places to get news, and decades before cable and streaming, there was far less to watch on TV. In the Philadelphia area we had the Holy Trinity of Channels 3, 6, and 10 (NBC, ABC, and CBS) plus whatever you could find on UHF: Channels 17, 29, and 48, whose fare ran heavily to Gilligan’s Island and The Flying Nun reruns, 1960s Japanese anime cartoons like Astro Boy and Marine Boy, and black-and-white movies from the 1950s and earlier. In that entertainment wasteland, why not peruse the papers to see what The Advertiser was advertising and The Recorder was recording?Delivering papers at a young age would be good for me, said my dad. When you were a kid, things that sounded frankly awful were always good for you.

My Own Private Book Club

Not as good as a book - it makes a very poor doorstop.

Wednesday, February 25, 2026

A Day in the Life of an American Paperboy, c. 1974

Monday, February 09, 2026

Saturday, January 31, 2026

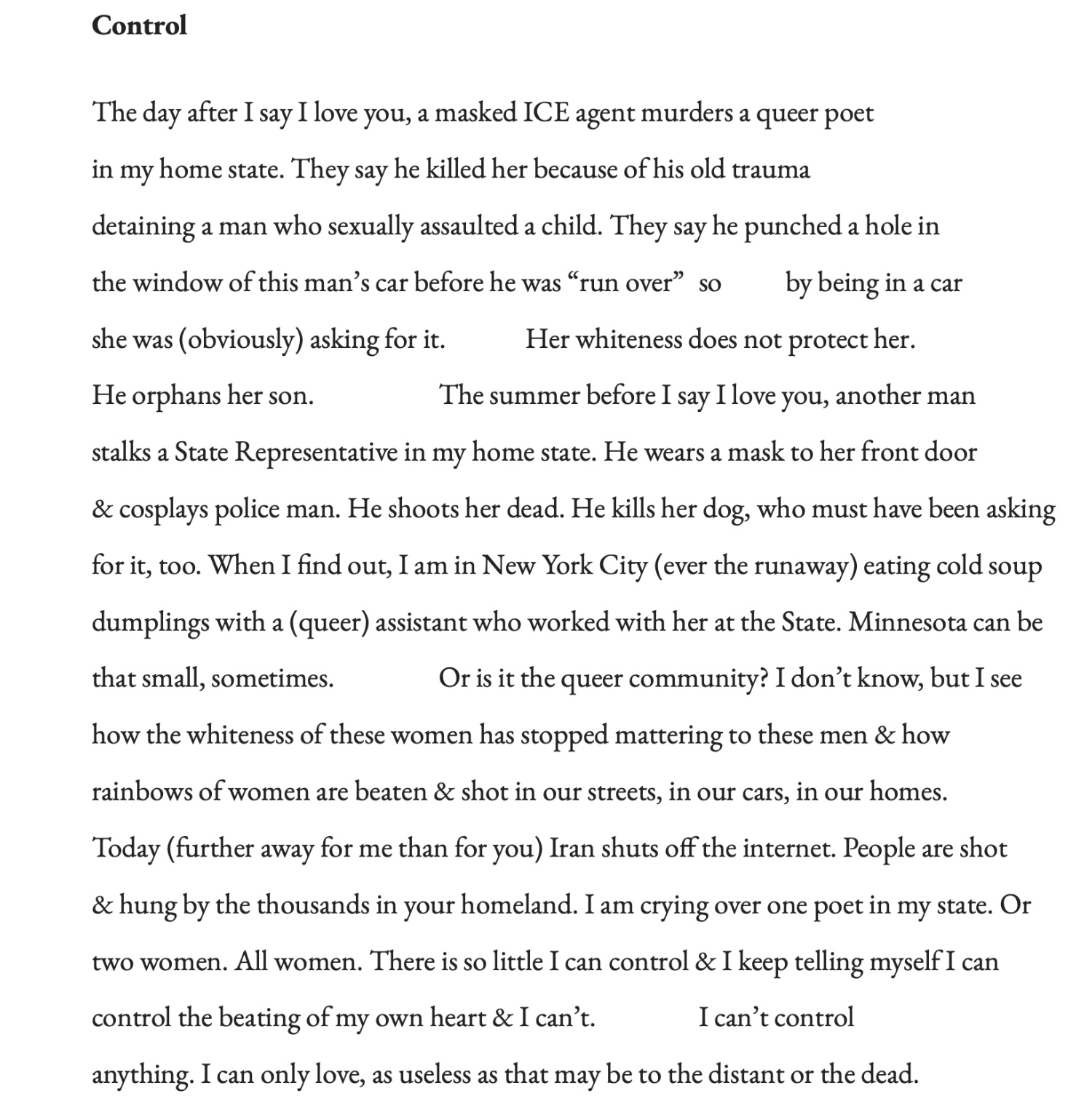

Hobart :: Songs in Case of Sudden Death

On a Wednesday I wonder if Bob Dylan will accompany my mangled form into the afterlife; the following Friday I imagine John Lennon. A week later, surrounded by shattered glass, a rusted guardrail impaling the awful tableau, I’m sure I’ll hear Nina Simone as I draw my final, ragged breath. There are now over one hundred songs on my “untimely death/car crash” playlist, all carefully selected in case I should perish in a macabre tangle of metal and gasoline on southbound M-39.

M-39 is a grey chute of concrete bisecting metro Detroit, a regular part of my commute. It chainsaws through urban decay and development alike, miles of new and crumbling brick, the shoulder a graveyard of discarded Big Gulps and broken 40s and containers for other beverages that never really quench your thirst. Five billboards featuring shark-eyed personal injury attorneys loom across the freeway, and I’m often fearful that their outsized, two-dimensional faces will be the last I see in this life. I can’t do much about what I see here, but the audio element is definitely within my grasp.“This is beyond morbid,” my husband, G, tells me when I inform him of my playlist. I shrug and add a few Miles Davis tracks, deciding some instrumentals might be nice. Lyrics sometimes devolve into underwhelming choruses: strings of baby or hey or oooh, less than ideal listening for the last moments of life.“God forbid a stupid remark on some podcast be the last thing I hear before I leave this world!” I say.This is the crux of it, really. It’s not just the thought of dying in a wreck in suburban grayscale that depresses me, it’s the notion that the soundtrack to my death would be so inane: a movie plug or fake laughter or an ad line punctuating my demise. Imagine a death scene in a movie, but the music isn’t Hans Zimmer or John Williams—it’s the jingle for Auto Zone.

Thursday, January 29, 2026

The Tavern at the End of History by Morris Collins (excerpt)

The afternoon that Jacob called, the Yitzhak Bloom Senior Curator of Modernist Paintings came down to Rachel’s office in the basement of the Museum of Jewish Art and asked her, as he sometimes did, if she wanted to go to lunch.

Rachel worked alone, in a room with a desk and a phone. It was a setup out of East Berlin, the interrogation chamber from every spy movie: bare floor, neon light tubes affixed to the ceiling, a metal desk in which all the drawers were locked, and two chairs, one she sat in and one she faced, though that one was always empty, and she was never sure whether she should feel like the prisoner or the interrogator. Beyond this, she had only a map of the galleries and a chart providing each painting on display with a numeric code. At first there had been a Monet print on the wall, as well as a framed Ansel Adams photograph leaning in the corner, so that the room felt less like an interrogation chamber than a high school guidance counselor’s office, but they both disappeared during her first week, and the room reaccrued its essential character. Several times she had moved the empty chair into the closet down the hall where the coffee machine was kept —if everything else could vanish, so could a chair—but it was always returned by the next day, sitting across from her, bare, somehow recriminatory, vaguely expectant.

So having another person in her space was always a little surprising, even if the curator, gazing at her with his usual mix of mild reproach and gauzy concern, seemed not abundantly different from the empty chair. Also, he would not cross into the room. He hesitated on the threshold as he asked her to lunch, brisk, polite, a little genteel and a little sweaty, dressed totally in seersucker.

For lunch they got sushi. “Who could eat anything hot in this weather?” the curator said, every time, no matter the season. Perhaps she was supposed to derive something meaningful from this. She did not like sushi that much, but enjoyed how long it took the curator to eat it. He was a precise man and he separated the chopsticks with a single clean snap, rubbed them together, locked them between his fingers and never once put them down or had to readjust them during the meal. He was dexterous and blond, fortyish, his face changed colors as he spoke, went from sallow to florid, his name was Simon, and because he had to avoid getting soy sauce on his seersucker suit, he took forever to eat.

He liked to ask her questions about her aspirations. “Would you want to work back upstairs?” “Did you ever intend to go into academia?” “Have you considered digital platforms?” Between questions he dipped his fish in soy sauce, raised it vertically, and then at the very last moment, in ridiculous slow motion, leaned in with his mouth already open like an ancient tortoise and closed his teeth around it. He didn’t much listen to her answers, but in her experience with curators, it was rare enough that he even asked the questions. After Trump’s election he had started coming by more often, ostensibly to check that she was doing all right, that this had not been the final blow. “You know,” he said. “The straw. The camel. After the year you’ve had.”

He’d hired her originally—she supposed—because they hit it off talking about Cubism in her interview, and she’d long ago noticed that his syntax matched his interests. He was a Cubist conversationalist. All fragment and implication. She liked it. The tenuous logic, the straight-on side-eye of a simple sentence. The way he referenced her grief only in euphemisms. She could pretend not to know what he meant.

This time, Rachel ordered miso soup and udon noodles. He looked concerned. “Deviation is the heart of progress,” she said and smiled and slurped soup and wiped her chin and then watched his eyes. Beneath Simon’s precision lurked, she felt sure, a simmering prissiness.

“Are you looking forward to our Lurio exhibit?” he asked.

Rachel had managed to ensnare a noodle with her chopsticks, but it was a very long noodle, and caught between sucking it slowly into her mouth while he watched or biting it, she chose to bite it. The severed half plopped limply back into her bowl. She smiled. Lurio was her specialty. A chapter from her dissertation on his depiction of desire, what she had called “subject-object intimacy,” in his early Paris portraits had been well published. Their standing collection and the coming show and all the opportunities for study and scholarship were originally why she had wanted to work at the museum. But since she’d been hired, over a year ago, no one had mentioned it, and it was only two years out. Did he imagine she’d stay in the basement for all that time, content and unconsulted?

“Of course,” she said. “I haven’t seen Juliet Goldman or Jewess on the Eve since I was a grad student.” These were both on almost permanent display at the Prado, where, as a student, she’d been given a three-month summer fellowship. She never knew just how much of her CV to remind him of in these conversations where the power dynamics remained inscrutable.

“Oh, those,” he said. “We’ll have them. Bit of concern where to put them. Wallwise. I don’t think we’ll go chronologically, but they’ll need some different backing. Early and all. Very red.”

“What are you thinking for themes?” Rachel had been curating the exhibit in her head for months now. Simon would insist, of course, on a thematic organization of his own devising, but for Lurio a chronological display would actually make sense: his fin de siècle affectations, followed by the period of silence and then, almost overnight, his sudden passionate adoption of what he’d been hiding ever since he changed his name from Lurtz: his eastern European Judaism. They could end with the last few works done in Canada after the war. The sequence of Enoch among the heavenly hosts, violent, shattering with Blakeian geometry and color. If these were, as most scholars claimed, the mournful eulogy to a lost world, she didn’t see it. In all of them Enoch, witness to the divine machine, seems struck not by wonder, but rage. Yes, she always thought of Blake; whatever hand or eye dreamed up the world must be monstrous. Enoch confronts the celestial hosts, all wearing capes of swastika red under an oppressive horizon of jutting lightning and glaring orange mountains. It’s supposed to be heaven, but if he believed in it, she couldn’t imagine how else Lurio would fashion hell.

“What are you thinking for themes?” she asked again. For the previous ten seconds, a huge green piece of a caterpillar roll had required the curator’s entire attention.

“Oh, right. Well, it’s early days you know. But probably going with Devotion and Temperament. Inner Storm, Outer Order. The Artist’s Journey. That kind of thing.”

Lurio had been into absinthe and hashish while in Paris, though he quit when it began hurting his health and slowing his output. Still, it was what everyone focused on. The Bohemian excess, the booze, the drugs, the naked muses.

From The Tavern at the End of History by Morris Collins.

Sunday, January 25, 2026

A Bridge Too Far ... On Alex Pretti by Robert Arnold

Sunday, January 18, 2026

Worry - Alexandra Tanner

Jules and Poppy are adult sisters who don’t like each other very much. Jules has a boring job and an apartment in New York City. Poppy arrives on her doorstep and moves in with her temporarily though both have strong misgivings about the arrangement. Poppy has terrible skin allergies and an attempted suicide in her past. They have a deeply dysfunctional relationship with each other and with their mother who has become a doomsday prepper and is involved in some sort of shady pyramid scheme.

Jules spends most of her time scrolling through the social media accounts of very odd right-wing, anti-vax, Jesus worshipping mothers. Poppy scratches her hives. They fight a lot, they are, without exception, shallow and unlikeable.

I waited for something to happen but nada. There was a lot of snappy patter that kept me working my way through to the totally unexpected and disturbing ending.

Monday, January 12, 2026

Terrible Things Are Happening Here

“Terrible things are happening outside. At any time of night and day, poor helpless people are being dragged out of their homes. They’re allowed to take only a knapsack and a little cash with them, and even then, they’re robbed of these possessions on the way. Families are torn apart; men, women and children are separated. Children come home from school to find that their parents have disappeared. Women return from shopping to find their houses sealed, their families gone. The Christians in Holland are also living in fear because their sons are being sent to Germany. Everyone is scared. Every night hundreds of planes pass over Holland on their way to German cities, to sow their bombs on German soil. Every hour hundreds, or maybe even thousands, of people are being killed in Russia and Africa. No one can keep out of the conflict, the entire world is at war, and even though the Allies are doing better, the end is nowhere in sight.”

Wednesday, January 07, 2026

Tourists!!

Panorama - by Derek Neal

The town had only one grocery store, and Steve wondered where the locals did their shopping. Certainly not here, but perhaps in a supermarket outside of town, one that required a car. Along with Julia, he picked up some Italian cheese, prosciutto, grapes, and a bottle of local wine, and they made their way up the hill to the house they’d rented for the week.The two friends from college were proud of themselves. They weren’t staying next to the sea with the rest of the tourists, but in a different village altogether, one that required a short bus ride and where no other passengers got off. In the village, the few streets that existed were carved into the hillside, each one so narrow that they were forced to walk behind one another, instead of side by side.It had been a long day, and they felt they deserved to indulge. They’d gone hiking high above the town, starting early and rising with the sun. The trail followed the curve of the hills, the open sea to one side, vineyards to the other. What lay before them not visible beyond a few yards. They heard fellow hikers before seeing them, but rarely was any Italian heard. When two groups passed each other, each group always smiled and let out a garbled “Buongiorno,” before reverting to their respective languages. Steve complied and mumbled “Ciao” a few times, but soon he began to feel like an imposter, playing at being Italian, or playing at being whatever it was people thought being Italian meant, and he resigned himself to nodding politely in response to the other travelers.Back at the house, they opened the windows to let the late afternoon sunshine in, and realized they could access a small platform via their own bedroom window. It seemed to be a sort of roof, but instead of a house below, there was a suspended passageway that you could pass beneath. Steve climbed through the open window, and from inside Julia passed him a plastic table, two chairs, and what they’d bought at the store. Once everything had been arranged, it was a sight to behold: on one side, the hills bathed in light from the low hanging sun, on the other, the pink and yellow hued town perched atop the blue sea; then there were the two of them, and a plate of rich, sumptuous food in the middle.They touched their wine glasses together, looked each other in the eye, and made a toast: “To Italy!”

Tuesday, January 06, 2026

Literary Hub’s Most Anticipated Books of 2026

This is a mammoth list of 314 books to read in the New Year, with something that will appeal to everyone. The titles that jumped out at me after a quick scan past the covers, without even reading any of the blurbs: a novel by Julian Barnes, a memoir by Mark Haddon, a biography of Larry McMurtry, Anne Enright’s new novel, historical fiction by Francine Prose, fiction by Deborah Levy, a new Ann Patchett, another unearthly delight byEmily St. John Mandel.